| |||

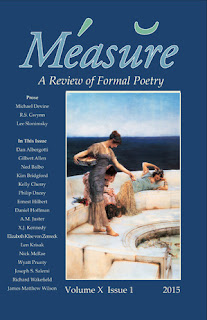

| A "coursing" mole. Courtesy of TheGuardian.com |

Excerpts from an interesting reflection on metaphor (http://hartzog.org) in Richard Wilbur's exquisite Spenserian sonnet, "Praise in Summer":

PRAISE IN SUMMER By Richard Wilbur

Obscurely yet most surely called to praise, As summer sometimes calls us all, I said The hills are heavens full of branching ways Where star-nosed moles fly overhead the dead; I said the trees are mines in air, I said See how the sparrow burrows in the sky! And then I wondered why this mad instead Perverts our praise to uncreation, why Such savor's in this wrenching things awry. Does sense so stale that it must needs derange The world to know it? To a praiseful eye Should it not be enough of fresh and strange That trees grow green, and moles can course in clay, And sparrows sweep the ceilings of our day?

This is a sonnet specifically about the motive for metaphor, but the motive for metaphor is the motive for all figures of speech, all tropes.

The Speaker in the poem feels called upon to praise the glories of summer. So he offers praise by making three statements that are whimsical and fantastic metaphors.

First, "I said The hills are heavens full of branching ways Where star-nosed moles fly overhead the dead;". Here's a statement that is made up of extended metaphors. The Speaker turns the world upside down and imagines the mole holes and tunnels under the ground as if they are a "series of branching ways in the sky(heavens) and the moles as birds flying in their tunnels. He also adds another metaphor--"star-nosed moles." The moles' noses are compared to the stars in the sky.

The second statement: "I said the trees are mines in air." The speaker continues with the basic reversal of perception: To view the earth and what's under the surface as the heavens and now to view the heavens as the earth, with the trees now viewed as if they were mine shafts burrowing into the heavens.

The third statement: "I said See how the sparrow burrows in the sky!" This statement completes the reversal of heaven and earth. The sparrows are compared to the moles. just as the moles are imagined as birds "flying" overhead the dead beneath the surface of the earth, so the sparrow's flying in the heavens is imagined as a mole burrowing in the sky.

Now comes the great reversal. Wilbur has used the sonnet form with one of its common structures: 6 lines and then 8. Notice the first 6 lines consist of praising the summer by means of his series of metaphors. But now he shifts the focus in the last 8 lines. Just as the speaker's imagination is in full flight, doing figure eights with metaphors, he suddenly stops short and questions what's he's just done. He's questioning the reason for metaphor--this strange bending of the language. He does it by means of two questions:

"And then I wondered why this mad instead Perverts our praise to uncreation, why Such savor's in this wrenching things awry."

The Speaker suddenly wonders what is the motive for metaphor. "Why this mad instead/Perverts our praise to uncreation..." Metaphor is a "mad instead" that "Perverts" praise for the summer--trees and the sky and birds into "uncreation"--metaphorical expressions like "trees are mines in air, "star-nosed moles fly overhead the dead." These images are not part of nature--creation, but the fanciful products of the Speaker's imagination--"uncreation." It is a substitution of one thing for another. A mole for a bird, a mine shaft for a tree trunk. Why not just call a bird a bird and a spade a spade? Notice however, that even in the act of questioning metaphor, the speaker uses one: "Mad" instead is a metaphor comparing the replacement of one thing by another to a crazy person--a personification to boot.

"why Such savor's in this wrenching things awry." The speaker asks another why question. Why is there such pleasure in making metaphor, in "this wrenching things awry." Again, in the act of questioning why there's "such savor's"--such pleasure--in the "mad instead," in turning the world upside down and viewing the heavens as if it were all the tunnels and burrows under the surface of the earth, and the underground as the heavens,--he can't escape using metaphorical language. The pleasure of metaphor is compared to "savor's"--a taste metaphor. The "mad instead" is a savory dish that brings pleasure to the palate. "Wrenching things awry" is also a metaphor, comparing metaphorical language to the act of twisting or bending some object out of shape. So he asks why do we get such pleasure in these language twisting games.

The speaker ends his ruminating on the motives for metaphor by asking two rhetorical questions.

Does sense so stale that it must needs derange The world to know it? To a praiseful eye Should it not be enough of fresh and strange That trees grow green, and moles can course in clay, And sparrows sweep the ceilings of our day?

Now we're getting to the point. It's a lovely ironic statement. Here is the motive for metaphor. The answer to the first rhetorical question is yes. Exactly. Sense is so stale that "it must needs derange the world to know it." In other words, ordinary perception is dull.

And the speaker shows us how dull by asking, "To a praiseful eye/ Should it not be enough of fresh and strange/ That trees grow green... " The irony should be clear. There is nothing fresh and strange about saying "trees grow green." It's a dead, cliched statement without insight or excitement--hardly any kind of "Praise."

An now the final irony. Even in the act of suggesting that we don't need the "mad instead" of metaphor--that it should be enough to talk straight and plain--to say a tree is green, he can't finish his thought without resorting to that same mad instead of metaphors: "and moles can course in clay, And sparrows sweep the ceilings of our day?

Moles "coursing in clay" is a metaphor comparing moles moving in their tunnels to boats or cars navigating a course. The act of sparrows flying in the sky is compared to the act of sweeping a floor with a broom. But a further metaphor--the floor becomes the ceiling.

So this poem, which attacks metaphor in favor of plain speech turns out to be a defense of metaphor. If we want to praise the summer or bring fresh insight into any aspect of human life, we do indeed need the "mad instead." Sense is so stale (another metaphor) that it must needs derange (metaphor) the world to know it. The mad instead of metaphor deranges the world, wrenches it awry out of its conventional patterns in order that we can see it again as "fresh and strange."

This blog post was inspired by a posting today by a Facebook friend who wonders whether she will "even get a dead-small-critter poem out of this?" (a squirrel had fallen down her chimney and was frantically trying to get out).

I'm almost certain she will. Go for it, Maryann!